The Art of Exception

English is an area of interest littered with edge cases. In preparation for addressing similar problems in the development of the Harper Chrome extension, I'm spending some time here reflecting on what I've learned by tackling the complex maze of English edge cases.

Harper is not alone, and there's a real chance that you'll have to work on exception-tolerant code. In that case, you will need to understand the why for some of the design decisions you encounter in the wild.

What Do I Mean By "Edge Case"?

An edge-case is a situation (that is often context-dependent) which results in incorrect behavior from a model, program, or theoretical framework. In conversations about the Harper Chrome extension, an "edge case" is where the extension improperly reads from or writes to a site's embedded text editor.

Most sites use <textarea /> or <input /> elements for text editing, but a number of sites (including WordPress, as you know) have complex WYSIWYG editors. Each behaves differently, which can cause problems with the aforementioned read/write loop. The problem: our users expect us to support all major text editors.

Err on the Side of Inaction

In Harper's core algorithm, we err on the side of false-negatives. This decision was derived from an observation made early on in the project's life cycle: people usually blame themselves for their own writing mistakes, unless the error is truly trivial.

All in, we get far more complaints about false-positives than false-negatives. Which is why we err on the side of inaction. If the algorithm thinks it's possible, but not certain an error was made, we suppress the report in case Harper is wrong.

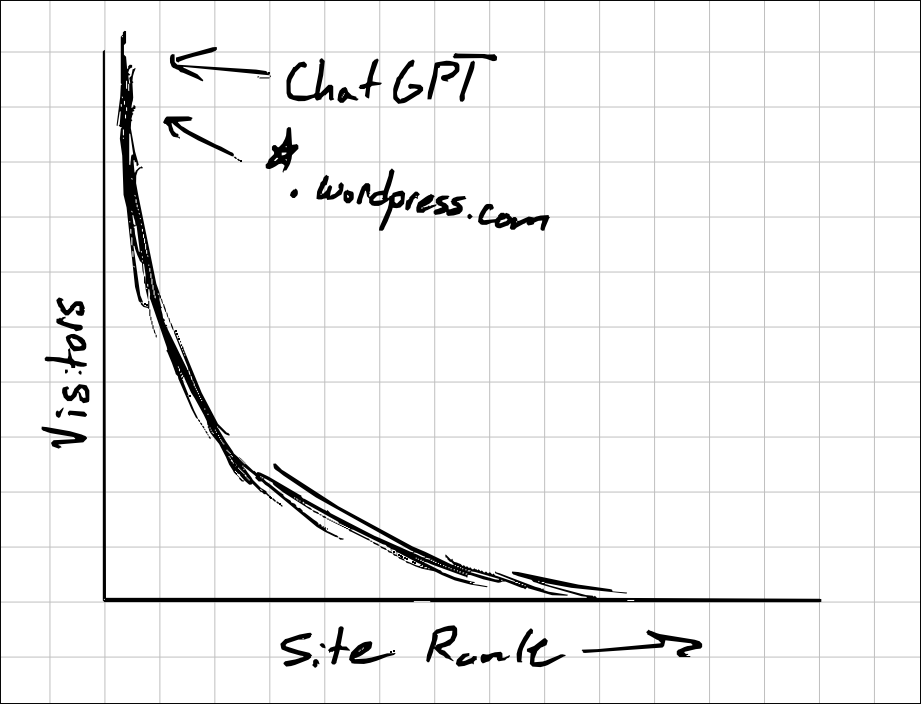

In the Chrome extension, we will be exemplifying this rule by only enabling it on a curated list of domains by default.

As site visits tend to follow a Pareto distribution, we can cover most traffic with just a few items in this list.

Make Tweaks Easy

When an edge case (which is almost always a false-positive) appears in Harper's core algorithm, it's usually in a pretty obvious spot. This is because we associate each lint output with a specific, easy-to-find module the core code.

In most cases, this is not verbose, specialized Rust code. Rather, it is an LLM-friendly DSL that is legible to most with even beginner-level programming experience. This combination of easy-to-read and easy-to-edit makes contributions from the community (regarding edge-cases) commonplace.

I aim to replicate this success in the Chrome extension's read/write capabilities by carefully documenting the architecture and working with third-parties to make the contributing process clearer and easier.

It Is an Art

There is a reason I call this an art. Design decisions in exception-tolerant systems stem from these two simple ideas, but they grow from an intuition developed by their maintainers. I'm not exactly sure how the Chrome extension will grow to handle edge cases. I'll be sure to come back here and detail them when I do.

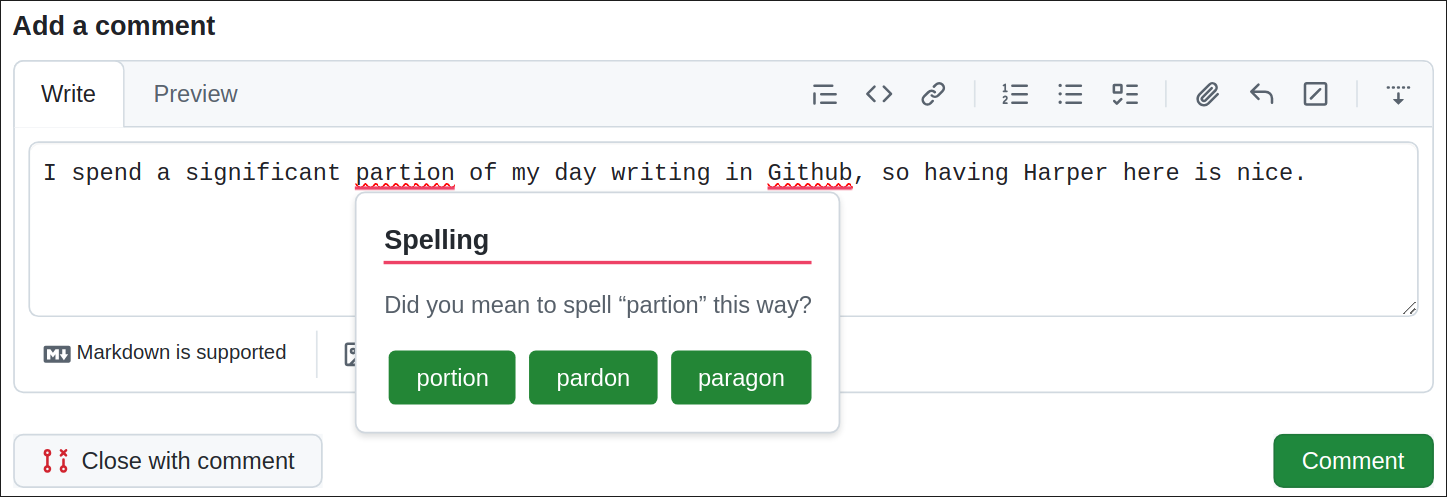

This post was proofread by Harper.

Comments

Other Stuff

Quantifying Hope on a Global Scale

An experiment on how to live in a seemingly hopeless world.

Do Not Type Your Notes

It didn't work for me, and if you reading this, it probably won't work for you either.

Local-First Software Is Easier to Scale

The title of this post is somewhat misleading. Local-first software rarely needs to be scaled at all.