Re: Collaboration Sucks

Earlier this week, I came across a really great post from a product engineer over at PostHog. If you haven't already, I highly recommend reading it. With the title "Collaboration sucks," I think it makes its message clear.

If you had shown this article to the Elijah Potter from a year ago, he would have agreed with most of what it says. I was of the strong opinion that collaboration was fundamentally counterproductive to getting sh*t done. Since then, I've completely changed my tune. While I don't believe collaboration is the secret weapon my professors in school made it out to be, I think it's essential to working on ambitious projects for a long time without burning out. Furthermore, at least for open source projects, I think it's critical for prioritization of work.

First, let's get something out of the way. Although the post title declared that collaboration in any form was bad, the meat and potatoes of the post have a slightly different tune. He merely said that it isn't that collaboration is bad, just that too much collaboration is bad. I can get behind this, but I still think there's more nuance lurking in the shadows.

I think Cook's post outlines many of the various ways collaboration can go wrong. I particularly enjoy the red flag examples he provides. I'd like to provide some examples of collaboration going right.

Since all of this is strictly related to Harper, it's possible that both these examples are only helpful to open source projects.

It Boosts Motivation

When I go a little bit too long without engaging with a member of the Harper user base, I start to feel a bit deflated. I start to forget who it is all for.

As a part of my own writing environment, Harper exists to make writing more fun and more human. I can think critically about my message while spending less time worrying about grammar or punctuation. For others, it poses to do all that without violating their privacy. It's great to hear from them, and how we can make our service even better.

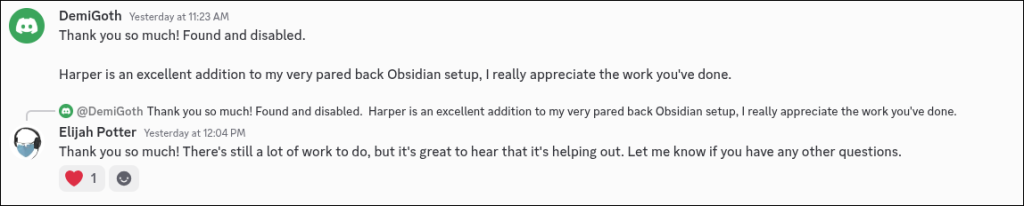

I know I'm doing something right when I'm acting as customer support and read a message like this. I feel empowered. Not only do I know what I am doing right, I feel highly motivated to keep doing that thing.

In Open Source, Your Collaborators Are Also Your Users

When working on open source software, especially one that values privacy, clearly stating a policy of being friendly to pull requests is obviously critical. For one, it makes it clear that bug fixes are welcome and will be swiftly reviewed. Less obvious is the feedback residing within the pull request.

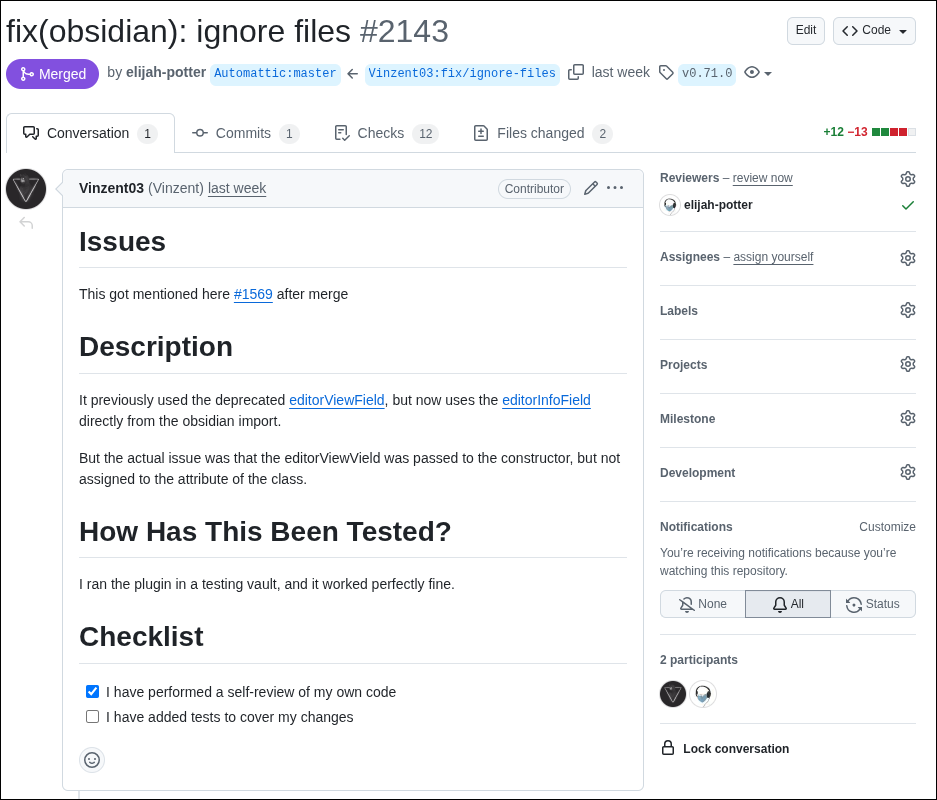

Here's an example. A user encountered an issue resulting from a change in Obsidian's API. Not only did he take the time to report the problem, he also went through the effort of implementing a fix. What does this tell us?

For one, it gives us an idea of where our documentation is sufficient. He was able to find the information needed to build the code and run it on his own machine. In the future, we don't need to prioritize the Obsidian plugin's documentation.

More importantly, however, is the fact that the feature was valuable enough for this user to spend time fixing it. If it is valuable for him, we can safely say that it is valuable for other users. Now that I have sufficient evidence, I might consider bringing similar functionality to other platforms, like our Chrome extension.

Collaborating in an open source context can be hugely informative, since your collaborators are also your users. In my experience, this is surprisingly uncommon, even in companies that claim to have a culture of feedback.

There Is Still Such a Thing As Too Much

While I've found these particular cases to be productivity-boosters, I understand that focusing too much on any one thing can be detrimental. First and foremost, the goal should be to ship as high a quality of software as possible, as soon as possible.

This post was proofread by Harper.

Comments

Other Stuff

Quantifying Hope on a Global Scale

An experiment on how to live in a seemingly hopeless world.

Local-First Software Is Easier to Scale

The title of this post is somewhat misleading. Local-first software rarely needs to be scaled at all.

Do Not Type Your Notes

It didn't work for me, and if you reading this, it probably won't work for you either.