Putting Harper in Your Browser

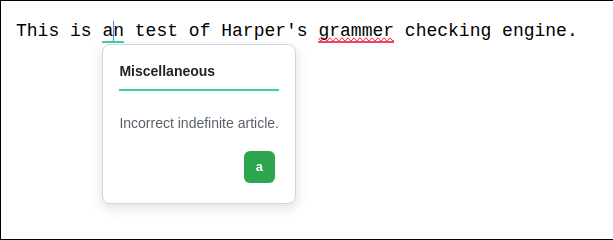

When our users install Harper, they should expect it to work anywhere they do. Whether they're writing up a blog post in WordPress, leaving a comment on Facebook, or messaging a loved one on WhatsApp, Harper should be there. Harper's core is extremely portable and it can run pretty much anywhere Rust can, so what's the big deal?

Why can't we just run Harper in the browser through a web extension?

Running Locally

There's a single complaint that I hear over and over again from people who use Grammarly or LanguageTool: they are both slow as molasses. The process of writing has slowly evolved to be more complex than it needs to be. With these tools, it writing looks like:

- Write a sentence.

- Wait for the grammar checker to run (which takes as many as four seconds).

- Fix the mistakes you made.

- Go back to step one.

The whole process reminds me of the copilot pause. This is part of why Harper is better than these other tools: it doesn't stop you from writing at the speed of thought. Our most ardent users tell us this all the time: it feels great to just write, error free.

How do we deliver grammar checking so quickly?

Instead of hosting huge Java codebases in the cloud, we ship our software straight to the user's device. Since there's no network request involved, we're able to put pixels on the screen faster than anyone else. That's not to mention the privacy implications.

Running Harper's engine locally in the browser presented some technical challenges.

I'm quite proud that our JavaScript library can be installed as simply as npm install harper.js.

In order for that to work as well as it does, I needed to develop a system for:

- Compiling our engine to WebAssembly.

- Shipping that engine to the browser.

- Instantiating the WebAssembly code.

- Build out the boilerplate necessary to make it feel native.

Steps one and four were easy.

I just slapped #[wasm_bindgen] tags on a Rust library and put on a pot of coffee.

Steaming coffee is vital for writing tedious JavaScript.

Steps two and three, however, were a little more difficult. The latest iteration of Google's extension standard, Manifest V3, places some heavy-handed rules on how executable code could be loaded. I won't bore you with the details here. Know that I spent many hours in JavaScript bundler hell.

Running Everywhere

Harper, nascent as it is, has the greatest market opportunity in the browser. Over 3.5 billion people use Chrome on a weekly basis. The plurality of knowledge workers spend most of their waking moments (as crushing as it sounds) in a web browser. Half of the time spent at desks today is spent writing.

In order to address this market segment, we need a Chrome extension. To lint text in the browser, I need a way to:

- Cleanly read text from input fields.

- Locate the pixel coordinates of grammatical errors.

- Render suggestions in popups.

- Cleanly replace text in input fields when a suggestion is selected.

Reading and Writing Text is Hard

The web may have standards, but there is nothing standard about it.

The "standard" way to input text is with a <textarea /> element.

Even so, most high-traffic sites implement their own text editors from scratch, using <div contenteditable="true" /> as a base.

Each of these cases required special care.

<textarea />

<textarea />s are hard for one reason: it is difficult to get a good understanding of what they look like.

I can obtain their content with input.value, but I can't directly infer the pixel coordinates of grammatical errors inside them.

When the Harper Chrome Extension is offered an <input /> or <textarea /> element to analyze, here's what it does.

- Creates a new

<div />. - Copies all styles from the provided element onto the

<div />. - Using

position: absolute;, it moves this<div />directly on top of the provided element. - Copies the content of the provided element into the

<div />. - Uses the Range API to turn the text indices emitted by Harper's engine into pixel coordinates on the

<div />.

Using this mirroring strategy works, but has performance implications and additional complexity to handle scrolling within the element.

<div contenteditable="true" />

Since elements in a contenteditable text editor (like Trix, Lexical, Gutenberg, etc.) actually exist in the DOM, I can just use the Range API to get pixel coordinates.

The trouble this time comes when I try to write a suggestion back into the editor.

Most documentation I could find suggests that you:

- Select the content of the element you wish to edit.

This can be done using

window.getSelection().addRange(). - Call

document.execCommand('insertText', null, "YOUR TEXT").

Much of this documentation acknowledges that document.execCommand is deprecated, but instructs you to use it anyway.

This is bad advice. Do not do this. I spent an embarrassing amount of time trying to get it to work consistently.

The better way to replace text programmatically comes directly from the W3C standard:

- Manually edit the DOM in the fashion outlined by the suggestion chosen by the user.

- Fire input events to instruct WYSIWYG editors to synchronize their internal state to the DOM.

I'll admit that this is an oversimplification. Much of the complexity here lays in determining which DOM nodes to edit or fire events on.

Read the Source of Truth

If you take one thing away from this post, it should be this: always read from the source of truth. There is a lot of faulty information out there, especially when it comes to creating complex interactions with opaque systems. If there is a source of truth, read it. It may look intimidating or seem unnecessarily verbose. It is that way for a reason.

This post was proofread by Harper.

Comments

Other Stuff

Markov Chains Are the Original Language Models

Back in my day, we used math for autocomplete.

Do Not Type Your Notes

It didn't work for me, and if you reading this, it probably won't work for you either.

Do Not Write with an LLM

I have been seeing an increasingly prevalent trend of people showing up in online spaces flaunting that they are writing with the assistance of AI. They seem to be proud of this. They shouldn't be.