Build a Wordle Solver Using Rust

The Game

Wordle is a relatively simple game. If you have ever played Mastermind, it should sound familiar. The goal is to figure out a mystery word with as few guesses as possible. The mystery word changes each day. Here are two example guesses.

After a guess, each letter’s color changes.

Green — The letter is correct. Yellow— The letter exists in the word, but not in that space. Gray — The letter does not exist in the word.

As you can see, there are a maximum of six guesses. If you cannot find the mystery word within six guesses, you lose. I have been competing with my grandmother each day to find the word in as few guesses as possible.

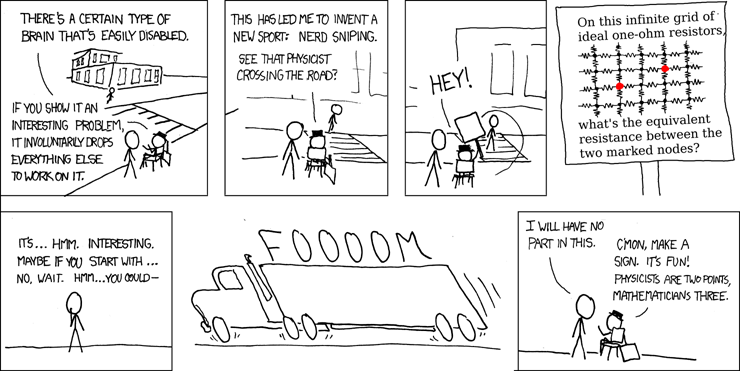

This totally nerd-sniped me. I felt an overwhelming urge to build an app that could, conceivably find the mystery word in as few guesses as possible.

How I Did It

First things first, we need a list of English words. I initially used the corncob list, but I found greater success with dwyl’s list.

For this project, I decided to use Rust, just because I felt most confident in my ability to make an MVP quickly.

Both the word lists I used are formatted as a sequence of individual words, separated by \n characters. On Windows (which is what I am using), they also have pesky those little \r characters.

Wordle is heavily focused on letters. I can remove items from the word list based on what letters I know aren’t in the mystery word (these are gray letters in-game), and I can remove items based what letters I know are in the mystery word (the orange or green letters), but in a lot of cases that still leaves a lot of possible words. I need to way to sort words based on how likely their letters are.

To do this, I count how frequently each letter appears in the word list, and give each word a score based on how frequently its components appear.

The first step in the program is to load the word list and count the letters:

// Store the total number of times a letter appears.

let mut letter_scores = HashMap::new();

// The final list of words. It will make like easier later in the program to store the words as Vec<char>.

let mut word_list = Vec::new();

let mut last_word = Vec::new();

let file = std::fs::read("corncob_lowercase.txt")?;

// Iterate through all the bytes in the wordlist file, ignoring all `\r` instances.

for letter in file {

let letter = letter as char;

match letter {

'\n' => {

word_list.push(last_word);

last_word = Vec::new();

}

'\r' => (),

_ => {

let entry = letter_scores.entry(letter).or_default();

*entry += 1;

last_word.push(letter);

}

}

}

Using the default HashMap (which uses SipHash, which isn’t great for single-character lookup), probably isn’t the best, performance-wise, but this is just a toy program, and doesn’t need to be the fastest thing in the world.

Next, we need to go through the word list, and eliminate words that contain gray letters. Here is a function that helps do that:

fn matches_found(

word: &[char],

found: &[char],

not: &[char],

must: &[char],

masks: &[Vec<char>],

) -> bool {

// Check if the word contains a letter we know *isn't* in the mystery. <-- The gray letters.

for c in not {

if word.contains(c) {

return false;

}

}

// Check if the word contains the letters we don't know the positions of, but know they are in the mystery word.. <-- The orange letters.

let mut found_letters = 0;

for c in must {

if word.contains(c) {

found_letters += 1;

}

}

if found_letters < must.len() {

return false;

}

// Check if the word has letters we know exist in the word, but not at the right spots. <-- The orange letters.

for mask in masks {

for i in 0..min(word.len(), mask.len()) {

if word[i] == mask[i] {

return false;

}

}

}

// Check if the word contains the already found (green) letters.

for i in 0..min(word.len(), found.len()) {

if found[i] != ' ' && word[i] != found[i] {

return false;

}

}

true

}

It accepts a few different char slices:

- Word: the word we want to check. Found: this is a slice containing the letters we have found (the green ones), with “ “ (space) characters in the locations we don’t know the character of.

- Not: this is a slice containing the letters we know aren’t in the mystery word.

- Must: this is a slice containing the letter we know are in the mystery word, but we don’t know the position of.

- Masks: this is a series of masks. We remove every word that has letters that match any mask here. This is useful for eliminating words in the wordlist that contain punctuation and for eliminating words that contain orange letters, but in positions we know they aren’t.

Now all we have to do is run each word in the word list and see if it matches our already known characters, updating the contents of each slice with new information after each guess.

Why You Should Care

This sounds like a useless problem. It is. There is no way this will benefit anyone other than me, and I definitely won’t use this when I’m actually competing with my grandmother.

Then why did you do it?

Useless answers to useless problems are useful. They teach us how to improve, without the pressure of real stakes. They are also just plain fun.

It’s also a reflection. How would you have approached this problem in the past? How has your thinking improved. Maybe it’s a bit magnanimous to say this little Wordle solver is the key to self reflection, but I don’t think it’s that far off.

A Reflection From Months Later

Hi! I am returning to this project months later with a few thoughts.

When I first wrote this article, I completely neglected to share my fitness test for each word. In hindsight, it's a good thing I didn't. It was the exact method 3Blue1Brown described as "naive" in his (fantastic) video on this very topic.

This post was proofread by Harper.

Comments

Other Stuff

Do Not Write with an LLM

I have been seeing an increasingly prevalent trend of people showing up in online spaces flaunting that they are writing with the assistance of AI. They seem to be proud of this. They shouldn't be.

My Writing Environment as a Software Engineer

Writing is one of life's greater joys. It's a mental workout that often brings me a level of clarity that is hard to find elsewhere.

Do Not Type Your Notes

It didn't work for me, and if you reading this, it probably won't work for you either.